Greene tells us that unless you want to mislead or distract someone, it is better not to argue. It is more effective to display with actions the point you intend to make. Human beings are rarely swayed by reason.

“The truth is generally seen, rarely heard.” – Baltasar Gracian

In 131 B.C., the Roman consul Publius Crassus Dives Mucianus needed a battling ram to take over the Greek town of Pergamu. But the engineer who was ordered to send him the ram spent a long time arguing about which ram should be used. He insisted that the smaller one would work better, using a series of technical explanations to back up his point. The consul received the ram he wanted, but was informed about the engineer’s arguments. The engineer was then summoned, and when he appeared before the Consul, he again repeated the same arguments he made before.

The Consul had hip stripped naked and had him beaten to death. The engineer transgressed against this law and suffered the consequences. He thought that by reason, he could sway his superior, or at least vindicate his own position. But he failed to recognize that doing so would only bring him a Pyrrhic victory. His argument offended the Consul, who was made to feel inferior. The engineer’s death was the only appropriate consolation for the Consul’s bruised ego.

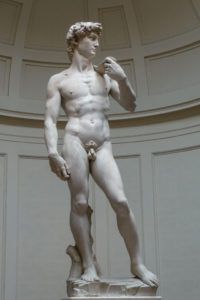

A story about Michelangelo shows us the power of using this law to your favor. In 1502, Florence, Italy, a huge slab of marble stone was ruined by an unskillful sculptor. But the mayor of Florence, Solderini, was determined to find a way of saving the block. He wanted to hire a master like Da Vinci to do the job, but none of the masters agreed. Michelangelo seized the opportunity. He said he could turn the slab into a statue of David with a sling in his hand. One day, as Michelangelo was applying the finishing touches, Solderini appeared. Solerdini thought of himself as someone with a refined taste for art, and looking at the statue from below, informed Michelangelo that the nose was too big.

Michelangelo didn’t argue; instead, he collected some marble dust (without Solderini noticing) and a chisel and acted as if he was working on the nose for a few minutes. Michelangelo knew that changing the nose could ruin the entire statue, but he couldn’t risk upsetting Solderini’s ego. As the marble dust dropped from Michelangelo’s hands gradually, Solderini believed that the nose had been changed. When Michelangelo asked him what he had thought when he was done, Solderini replied: ““I like it better, you’ve made it come alive.”

But sometimes, arguing can get you out of trouble. Victor Lustig, the notorious swindler, saved his own life by doing so. One day, a sheriff appeared outside his door, accusing him of ripping him off. Lustig has sold him a machine that was supposed to create money, but it did no such thing. The sheriff was infuriated and was out for revenge. But Lustig calmly expressed disbelief at the sheriff’s accusation.

Lustig heard a knock on the door. When he opened it he was looking down the barrel of a gun. “What seems to be the problem?” he calmly asked. “You son of a bitch,” yelled the sheriff, “I’m going to kill you. You conned me with that damn box of yours!” Lustig feigned confusion. “You mean it’s not working?” he asked. “You know it’s not working,” replied the sheriff. “But that’s impossible,” said Lustig. “There’s no way it couldn’t be working. Did you operate it properly?” “I did exactly what you told me to do,” said the sheriff. “No, you must have done something wrong,” said Lustig. The argument went in circles. The barrel of the gun was gently lowered.

Robert Greene, The 48 Laws of Power

Lustig then went to work on phase two. He told the sheriff that he would give him back his money and would go take a look at the machine himself. Lustig took out a hundred one-hundred-dollar bills and told the sheriff to relax and enjoy the weekend. The sheriff, confused, reluctantly took the money and left. Days later, Lustig received the news he had been waiting for. The sheriff was arrested for paying with counterfeit money and was taken to jail.

Read The 48 Laws of Power

If you’re interested in exploring the darker parts of human psychology that most people ignore, consider reading this short book The Dichotomy of the Self.