P.T Barnum

The Chinese general, Chuko Liang, had a great reputation. During the war of the Three Kingdoms (A.D 207-265), he dispatched his large army to a far away camp, while he stayed in a small town with only a few soldiers. Suddenly, a vast army of 150,000 soldiers led by Sima Yi approached his city’s walls. But Liang did not panic, he ordered his soldiers to take their flags down, open the city’s gates, and hide. Liang himself sat on the most visible part of his city’s walls.

He lit some incense and played a flute in a Taoist robe, acting oblivious to the army that was approaching. As Sima Yi and his troops got closer, it seemed like he would finally bring an end to Liang, but when he saw the great general in his relaxed position on top of the wall, he paused. Moments later, he ordered his troops to retreat as quickly as possible. Liang’s reputation saved him and his city.

For, as Cicero says, even those who argue against fame still want the books they write against it to bear their name in the title and hope to become famous for despising it. Everything else is subject to barter: we will let our friends have our goods and our lives if need be; but a case of sharing our fame and making someone else the gift of our reputation is hardly to be found.

– Montaigne, 1533-1592

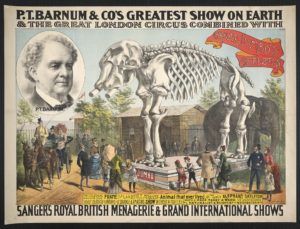

In the former example, Greene shows us how powerful cultivating a great reputation can be. In the following example, he shows us how one man, P.T Barnum, was able to become successful by destroying another man’s reputation and building his own through a series of a simple steps.

Young and unestablished, P.T Barnum decided to build his reputation as a great American showman by buying the American Museum in Manhattan. But Barnum had no money, and the museum’s asking price was $15,000. Still, Barnum persisted and arranged an agreement that would work through guarantees and references rather than cash up front. The owners were on the verge of completing the deal, but in the final moments pulled out. Peale’s museum was able to secure the purchase of the museum and its collections because of Peale’s superior reputation.

Barnum’s only move at this point was to try to ruin Peale’s reputation. He did so by first sending the newspapers letters that accused the owners of the museum a bunch of “broken-down bank directors” who were incompetent. He warned the public about buying Peale’s stock, and as a result of the campaign, Peale’s stock plummeted, and the American Museum was sold to Barnum instead. Peale needed years to recover his reputation and did so by catering to fans of “highbrow” scientific entertainment, positioning Barnum’s product as vulgar in comparison.

One of Peale’s big attractions was Mesmerism (hypnotism), and it enjoyed a lengthy period of success. But Barnum decided to ruin Peale’s reputation again by taunting him. He acted like a hypnotist himself and parodied Peale’s act for weeks, until the Peale’s show could no longer be taken seriously. Within a few weeks, Peale’s attendance plummeted, and the show was stopped. Barnum continued to enhance his reputation over the years while Peale was never able to recover his.

There are two steps that could be taken to build your own reputation when you don’t have one. First, destroy your rival’s reputation. When you sow doubt, it will harm your opponent no matter what he does. And If he fights back, he reinforces the suspicion. Even if he doesn’t, people will wonder why he isn’t defending himself and it will reinforce the suspicion more.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because this tactic is used regularly in the political arena. A weaker candidate builds himself up by creating rumors about his opponent, regardless of whether they are true.

Read The 48 Laws of Power

If you’re interested in exploring the darker parts of human psychology that most people ignore, consider reading this short book The Dichotomy of the Self.