Table of Contents

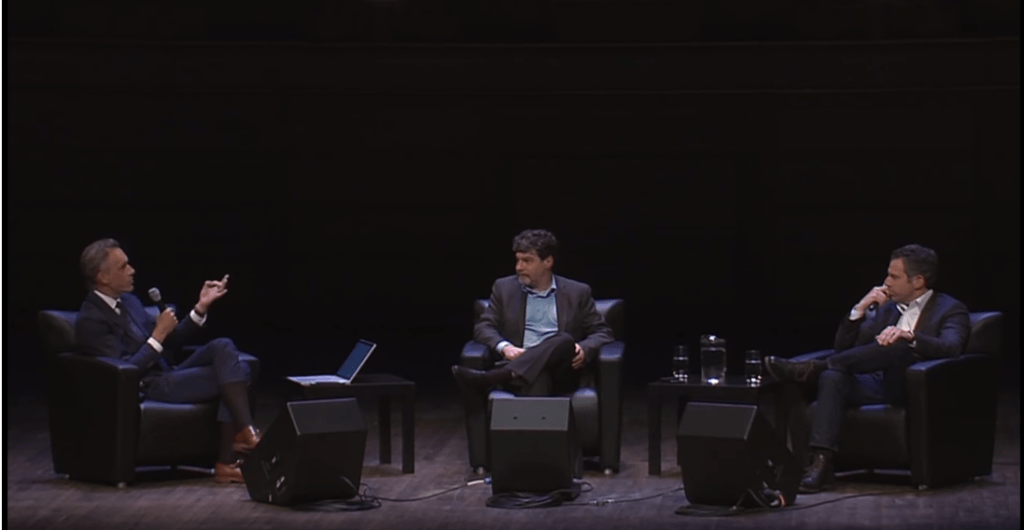

Peterson vs Harris – Vancouver (Part 1)Jordan Peterson first debated Sam Harris on a podcast when the two disagreed about the definition of “truth”. Despite their differences, they many common positions. Both favor free speech over political correctness and believe in the existence of absolute moral truths. And both agree that a literal interpretation of scripture is counter-productive. In fact, what made the first Vancouver debate interesting was seeing them converge on some topics instead of disagreeing about everything, and what made it even more interesting was seeing exactly where they disagreed. This conversational pattern remained consistent across the series of five debates they had outside the U.S (so far).

The Root of the Disagreement

Peterson and Harris disagree about two fundamental propositions. The first is whether religious texts are still relevant today, and the second is whether we ought to use rationality as the only standard to judge moral propositions. Harris believes that religions may have been useful at some point but are no longer capable of guiding our moral intuitions about modern problems. And he also believes that we should base our moral systems on rationality and facts. Peterson is less optimistic about the power of rationality, let alone in the hands of flawed human beings. That is why he is not willing to throw out “the baby with bathwater” (an overused statement in their debate). Peterson believes that while imperfect – Christianity has acted as a precursor for sustainable political systems – something atheism has historically been unsuccessful at doing.

Peterson draws on historical examples (Nazism, Communism) and shows that our previous attempts to subvert religious influence completely has resulted in genocidal totalitarian regimes. The fact that our attempts have been a complete failure should force us to reconsider the proposition that religions can be replaced by rationality. Christianity, for example, seems to serve a function that is critical for staving totalitarianism. Since its central message is the communication of truth (The Word, Logos)– it is the perfect antidote to the innate decadence of totalitarian regimes. Since true speech commands top position in the dominance hierarchy of values, it gives rise to self-correcting political systems that do not fall prey to power-hungry bureaucrats.

Further, our experiences in our short life span (relative to existence of ancient structures such as the dominance hierarchy, religion, etc…) are insufficient – they cannot illuminate enough truths about the nature of reality. Peterson thinks that we are too complex to be able to guide ourselves by using a top-down rational approach. Moral systems are emergent, they develop organically. He cites Piaget’s studies on how children naturally develop moral systems bottom-up through play.

Unlike Harris, who believes that is possible to use rationality as the framework to develop moral systems – Peterson thinks that most people need religion, or at least a functional interpretation of it that is preferably not literal. Since reality is complex to navigate, and many people either are incapable of devoting the work to be develop their own moral rules, or do not have the time for it, religion serves as a functional and important foundation.

While Harris is clearly right that ancient religious texts are a poor substitute for moral education when it comes to solving modern issues, his position becomes weaker when we take into consideration how feasible it is to expect most people in society to rationally construct their moral viewpoints on everything from scratch.

In fact, Peterson agrees when Harris accuses him of insinuating that less intelligent people need religion more than intelligent people do. Peterson justifies his position by making a pragmatic argument. He agrees that Harris’ idealism may be perfect theoretically but implementing it has proved to be very tricky in the past – and it’s not clear how we can avoid making a catastrophic error if we attempt the same experiment in the future.

To give an example for why he agreed with Harris’ accusation, Peterson asserts that is far better for people with below average intelligence to be conservative. His logic is straightforward. If some people have a sub-standard ability to navigate through complex problems, then they will find it difficult to accurately navigate complex problems about morality. It is then wiser for them to adopt conventional ideas as they are at least somewhat effective.

But of course, he acknowledges that clinging to norms can be counter-productive. There are times when doing the conventional thing works, but sometimes you are required to be more innovative – when reality isn’t stable or predictable. In which case, it is far better to not be conservative or conventional. It would be more advantageous to be open to new ideas because you will then be able to adapt better. This is especially relevant to today’s world where conventional ways of doing things are getting disrupted more rapidly.

Thus, Peterson rejects Harris’ position for two reasons. One, it’s not clear that rationalism can get us to moral truths that will sustain the survival of our species. Two, it’s not obvious that the hole that religion will leave behind can be filled by a benign alternative.

This isn’t a deadlock that can easily be resolved. Both have solid reasons for their respective viewpoints that I will talk more about in this and other posts but looking at it objectively – I believe the question should be more tightly defined. And this is sort of what Peterson hinted at when he suggested that being conventional works for some people more than others. It means that Peterson recognizes that in certain cases, it is far more important to rely on facts to make decisions. And as he makes clear, it’s not that facts have no place in moral considerations, it is that they are insufficient.

Metaphorical Truth

What he is trying to do is find the other things that are also relevant to moral considerations. Metaphorical truths (a term coined by Bret Weinstein) are one of those things.

Metaphorical truths are things you believe in that may be literally false, but carry some practical benefit. For example, it’s better to believe that all guns are loaded if you want to avoid a gun accident even if your belief isn’t literally true (Some guns are unloaded).

And perhaps this is where Harris’ and Peterson’s disagreement is most crucial. Even if Harris concedes that we are not capable of constructing a functional moral system by only using facts and rationality, that still doesn’t say anything about the utility of metaphorical truths. To Harris, metaphorical truths are open to multiple interpretations. The Hindus and Buddhists have different metaphorical understandings of the nature of evil, for example – and the fact that these understandings are different from those of the monotheistic religions (Christianity, Islam, Judaism), means that the metaphorical truths themselves are insufficient. There must be something deeper than religious mythology itself that gives rise to sustainable belief systems.

Harris doesn’t claim to know what that is exactly, but takes issue with two things that Peterson seems to do. One, if other metaphorical truths exist and are functional, then why is Peterson partial towards the Christian myth in particular? And the second concern is Peterson’s ambiguous position about whether he believes in God.

Why Christianity?

Harris’ issue with Peterson’s position is that he singles out Christianity from the set of belief systems, and there’s no reason to assume that the Christian story is any more valid than other stories.

Peterson has explained his belief in Christianity and God in several different ways and as he enthusiastically admits – it’s not simple. But it seems to me that his justification always gravitates to the following fundamental presuppositions. The first is his acknowledgement of Christianity’s role in shaping his own moral intuitions, in addition to the legal and political frameworks of western nations. Peterson believes that democratic systems are superior to alternatives – precisely because of free speech is the core mechanism underlying democratic systems. Since free speech is central to Christianity, he cannot but identify Christianity as the precursor to the only sustainable political system we know of today.

The second presupposition concerns the nature of “belief”. To Harris, beliefs represent what you think. But to Peterson, what you think you believe and what you say you believe doesn’t matter. What matters is how you act.

And according to Peterson, both he and Harris act as if God exists. They are both in pursuit of truth and believe that free speech is the mechanism by which to obtain it. They believe in the primacy of truth over power.

Peterson’s Definition of God

Harris and many others have accused Peterson of not having a clear position on whether he believes God exists. This is a question that Peterson has (to Harris) avoided in the past by stating that it’s not obvious what people mean by belief or what they mean by God or whether what they mean and what he thinks are the same thing.

This brings us to a key point in the debate, where Harris presses Peterson on his position about God. And Peterson proceeds with a lengthy explanation of his notion of God. This was the exchange that took place.

SH: What do you mean by God?

JP: I’m going to tell you some of the things I mean by God.

Here are some propositions…

God is how we imaginatively and collectively represent the existence and action of consciousness across time as the most real aspects of existence manifest themselves across the longest of timeframes but are not necessarily apprehensible as objects in the here and now.

What that means in some sense is that you have conceptions of reality built into your biological and metaphysical structure that are a consequence of a process of evolution that occurred over unbelievably vast expanses of time and that structure your perceptions of reality in ways that it wouldn’t be structured if you only lived for the amount time you were going to live. That’s also part of the problem of deriving value from facts, because you are evanescent, and you can’t derive the right values from facts as they portray themselves to you in your lifespan which is why you have a biological structure that is 3.5 billion years old.

God is that which eternally dies and is reborn in pursuit of higher being and truth. That’s a fundamental element of hero mythology. God is the highest value in the hierarchy of values.

God is what calls and responds to the eternal call to adventure.

God is the voice of conscience.

God is the source of judgment and mercy and guilt.

God is the future to which we make sacrifices, and something akin to the transcendal repository of reputation.

Here’s a cool one if you’re an evolutionary biologist.

God is that which selects among men in the eternal hierarchy of men. Men arrange themselves into hierarchies, and men rise in the hierarchy and there’s principles that are important that determine the probability of their rise and those principles aren’t tyrannical power. That’s something like the ability to articulate truth, be competent, and make appropriate moral judgments. If you do that in a given situation then all the other men will vote you up the hierarchy and this will increase your reproductive fitness, and the operations of this process ross time is codified in the notion “god the father”.

It’s also the same thing that makes men attractive to women because women peel off the male hierarchy, and what should be on top is partly tyranny, but the real answer is the ability to use truthful speech in the service of well-being. And that’s something that operates across vast expanses of time and plays a role in selection itself which makes it a fundamental reality.

But Harris wasn’t very impressed, and understandably so. Harris has spent many years debating proponents of God and religion – so to him, twisting the traditional definition of God is misleading. Harris accuses Peterson of using a loose definition of God and being unambiguous about his belief in one as ways to evade the obvious question.

Harris is annoyed because he feels Peterson is needlessly giving credibility to ideas that shouldn’t be revived by acknowledging that scripture can be useful. And that his belief in his own intuitions about God will mislead people into believing a supernatural God – that has no place in rational discussion.

But Peterson denies that a traditional definition of God exists, pointing out that it in some key texts, we are cautioned against defining God too tightly, or even defining him at all. Peterson then acknowledges that it is indeed true that we are confused about the nature of God – but the fact that so many people have responded positively to his definition of God may suggest that we contain the same intuitions of what God is, but many have been unable to articulate it properly – a job he seems to have done better than most.

The God Sam Harris is talking about cares about what you do privately, and he expects Peterson to agree with Harris’ conception of God. Going back to the discussion.

SH: I didn’t hear about a god who would care if you masturbated.

JP: Depends on what it stops you from doing.

SH: Important to do things other than masturbate…which is harder than it sounds. I’m not hearing a personal God that most people believe in. what percentage agree with your idea of God?

JP: It’s not so clear, they may have the intuitions but theyre not articulated well.

SH: What about ghosts? They’re an archetype (survival of death). We know what people mean usually when they talk about ghosts. to you, ghosts can be your relationship to the unseen. So I of course have a relationship to the unseen so I believe in ghosts, but that’s not what most people mean…

JP: But you cannot simplify God to that extent.

SH: But we know that it isn’t the god most ppl don’t believe in.

JP: I was asked what God I believe in.

SH: But your definition robs god of its traditional meaning.

JP: Wait, let’s not talk about the traditional meaning of God, there are cautions against defining God too tightly if at all, there are no traditional understandings of God. You’re not even supposed to utter the name of God.

BW: I don’t believe in a supernatural God but the God Peterson described I have no difficulty understanding why he would care if you did masturbate and how he could answer prayers. So it will be interesting, we (me and Jordan) haven’t talked about this. If I get from him a mechanism for this action, if he could tell me what I heard, it would suggest to me that we’re not just making up stories here.

JP: Let’s imagine the hellish situation you laid out but with an extra twist. Build in intent into it. The Hell isn’t a victim of massacres but someone who did something wrong. You sit near your bed and you confess to yourself: I really wanna know what I did wrong, and I wanna do what I can do to make it right and will do anything that manifests itself to me. It will give you answer, and it will not be answer you like.

SH: This is a process I am familiar with but requires to supernatural justification.

JP: But I wasn’t trying to give u a supernatural explanation. I was giving you an instance of prayer that worked.

SH: that’s fully understandable in terms of human psychology and…

JP: It’s not really understandable because we don’t know where the answer comes from.

SH: Well, we don’t know where anything comes from.

JP: That’s true!

SH: Yeah but one thing we know for sure is that the person who wrote the bible doesn’t know either.

JP: it’s not obvious what people know or don’t know.

BW: But we understand that these things could have evolved into something useful even if we don’t know how.

Weinstein makes an important point here that illustrates how Harris and Peterson diverge most fundamentally. Harris thinks we know more about human behavior than Peterson thinks we do. When Harris, frustrated by Peterson’s objection to us being able to understand where so-called answers to our prayers comes from, retorts angrily “we don’t know where anything comes from” and Peterson replies with an emphatic and somewhat comical “That’s true!”, we get a simplistic summary of how their epistemological disagreement – in so small part – led them to very different conclusions.

Peterson is again skeptical that we know anything about how our conscious experiences are formulated. Beyond a purely descriptive physiological understanding of brain activity, we know very little about how our brain works. Peterson thus views religion as an inevitable evolutionary consequence that simplifies reality for us so that we are able to function in it more harmoniously – that’s why Weinstein referred to religion as a heuristic when clarifying Peterson’s position in the debate. Harris, however, draws a clear line between what can be considered creative products of our imagination and what could be considered evolutionarily advantageous. Of course, it’s not because he believes religion could have been evolutionarily advantageous, but he believes that religion has been far more harmful than beneficial for humanity.

Multiple Interpretations

SH: This comes from your attachment to Christianity, but Hinduism and Buddhism have completely different understanding. Good and evil don’t have the same meaning in the east, to them, evil is just ignorance.

JP: Then you haven’t met any evil people.

SH: Fine, then you’re saying they’re wrong. But there are billions living according to completely different understandings of good and evil and their systems work. Presumably Hinduism is useful to them, and if as a matter of doctrine is irreconcilable with Christianity, then there must be a deeper level of reality that explains why they both work that can’t be reduced to either being true.

JP: Nothing wrong with that objection. But this is what leads to nihilism. What Nietzsche said that it’s hard to see your belief system is shattered by another one, but it’s even worse when your belief in belief systems themselves is shattered. you say I approach this from a Christian perspective, but I also address the postmodern “multiple interpretation” problem, and the answer you allude to in the moral landscape, and it’s part of the basis of your argument, why these things need to be grounded by facts. that’s part of the answer to infinite number of interpretations.

In maps of meaning, I tried to do what E.O Wilson recommended, a consilience approach.

From this Wikipedia article, In science and history, consilience (also convergence of evidence or concordance of evidence) refers to the principle that evidence from independent, unrelated sources can “converge” on strong conclusions. That is, when multiple sources of evidence are in agreement, the conclusion can be very strong even when none of the individual sources of evidence is significantly so on its own. Most established scientific knowledge is supported by a convergence of evidence: if not, the evidence is comparatively weak, and there will not likely be a strong scientific consensus.

I looked at multiple religious systems, Christianity, evolutionary biology, philosophy, neuroscience, and the literature on emotion and motivation and the literature on play and I tried to see where there was a pattern that repeated across all dimensions of evaluation which is exactly what you do when you use your five senses.

My proposition was that if the pattern manifests in 6 different places, it reduces the chances that I have a deluded interpretation of reality.

SH: Yes, but different conceptions of evil exist across cultures.

JP: Then how can you agree with what constitutes bad in the moral landscape?

There are either universal intuitions or there aren’t.

BW: Are some intuitions universal?

SH: Sure, but they’re deeper than religions.

JP: The problem I have with your argument is that you assume there is an unmediated fact when there is none.

SH: Yes, even facts aren’t unmediated facts.

JP: The reality of Protons is always real, moral facts are different. But some moral intuitions are facts. The superiority of heaven over hell, what you claim in your book.

SH: I’m only concerned with the misleading way you define god.

JP: If you mean we’re confused by the nature of god then yes. I never said what I talk about is like what other people talk about. It’s not a justifiable criticism.

SH: It’s a criticism because it gets in the way of us communicating honestly about ideas. It takes you 20 mins to admit that the bible is filled with barbaric nonsense.

JP: I don’t think it took me 20 minutes to admit. u want a one second answer? Sorry, not gonna happen.

SH: Take the question, do you think Christ was resurrected? It shouldn’t take you two days to answer. How about “almost certainly not” for an answer?

JP: That’s a fine answer, but the problem doesn’t go away.

SH: Which means what?

JP: I don’t know. people think I’m evading the question. I’m not, people have been arguing about this for thousands of years.

The Utility of God

The final part of the debate focused on whether accepting Peterson’s definition of God would allow you to intelligibly understand why He would care about what you did in private. Bret Weinstein was interested in experimenting with Peterson’s definition of God and tried to independently imagine a situation where he would share Peterson’s intuition for why God would care about what you did in private. This is important because it addresses Sam Harris’ main objection against Peterson’s definition of God, namely, that Peterson could have just as easily defined him differently.

Harris doesn’t see what exactly about Peterson’s definition is more accurate than any other interpretations that others have about God. As for Peterson – he doesn’t in fact claim to know the correct definition of God, but he does believe that his metaphorical understanding of God is more intuitive than Sam gives him credit for. Indeed, the fact that people (including atheists) who have found his lectures about God convincing suggests that Peterson’s intuition is not only his own but is shared by others.

Jung’s idea that we share a universal, subconscious understanding of archetypes is Peterson’s presupposition here. Peterson thinks that the power of stories and the ideas communicated through them are deeper and more profound than what we conjure up through conscious, rational, thinking.

If Weinstein, an atheist, finds Peterson’s intuition about God more convincing and useful as a mechanism than the supernatural, traditional intuition of God – then this would give Peterson’s argument more credibility.

BW: Some people are really interested if God cares if you masturbate.

SH: You wanna end this on masturbation? The floor is yours.

Bret: Let’s assume a scenario where you are afraid of masturbating because of God. What happens?

SH: Nothing. Okay there can be some wisdom in not masturbated.

BW: Let’s assume that a certain amount of masturbation was stopped, this would cause people to want to satisfy their urges by more urgently searching for a mate. This increases the human population. If we can agree that this story resulted in a mechanistic adaptation. And then we would be able to understand why God does care why you masturbate, because God is a set of stories. But sometimes it’s better not to procreate, like if the population is growing too rapidly. If you have no tools to criticize it, you won’t know that.

SH: the problem is that useful fictions are limited, because they become irrelevant but useful truths aren’t. We can agree that there’s reason to worry about porn, for example, especially its availability to teens. It’s worrisome. But you don’t need mythology to do that.

JP: Then how do you it? We have no mechanism.

SH: Educational interventions.

JP: These barely work for sex ed. People aren’t nearly as amenable to behavioural changes because of rational educational interventions as you might hope. I mean that’s part and parcel of the broad clinical literature.

(Another example of Peterson’s scepticism of the completeness of our knowledge structures. It’s not clear that an interventionist, top-down approach can work.)

SH: They’re not as amenable to dogmatic intrusions either.

JP: Yeah, but they are, and that might be a problem because there are problems with that.

SH: Even if you could make the case that a dogmatic attachment to one or another religion is better than being truly secular or rational, its vulnerable to every next thing we find out. If you go back centuries earlier, you can figure that people who adhered to certain hygienic practices because of religion predated our discovery of the germ theory of disease, but once you know the facts, the whole edifice comes crashing down.

JP: But you may not want to destroy the whole edifice. It’s not like Im an enemy of the enlightenment. But it’s not like everyone was ignorant until the enlightenment came around. There was a lengthy developmental history that is radically underplayed by people who ground it purely in rationality

SH: My point is that we should agree that having a world view that continues with an honest engagement with reality is better than anchoring our world view to people with no insights that we don’t have or superior principles.

JP: It depends on the principles. There are higher order principles that you also appear to rely on (profound moral intuitions) in the moral landscape. That’s what im trying to address, where these intuitions come from. To you, the facts are there and you can extract value from them, and it’s better than nihilism, fair enough. But the facts as they have been around for a very long time, say 3.5 billion years. and it is the operation of those facts on life that has produced the a priori implicit interpretive structures that guide our interaction with the facts. and those a priori implicit structures that have emerged out of this evolutionary course have a structure that mediates between us and the facts that cannot be derived from the facts at hand. So what is that structure? Important to get that right. You use it for the source of moral intuition.

SH: Let’s table this for tomorrow night.