Table of Contents

Summary

The Hero with a Thousand Faces is a book about the stories of the past, and our deep human longing to connect with the ancestral spirit that informs these stories. Campbell informs us that there are many different ways of interpreting the purpose of mythology, but essentially they are a “conveyance, vehicle, to use in order to think, to move forward through life.”

Stories contain a structure within them that isn’t merely present in mythology, but in any form of narrative representation, including movies, novels, and fairy tales. In a series of three articles, I will discuss the different parts of The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and what the essential parts of a story is, and what universal mythological universal themes are worth learning about and understanding.

“It is not too much to say that lack of compelling and unpredictable heroic stories can deaden an individual’s and a culture’s overall creative life—can pulverize it right down to powder. It is not too much to say that an abundance of compelling and unpredictable heroic stories can re-enspirit and awaken a drowsing psyche and culture, filling both with much-needed vitality and novel vision.”

Prologue: The Monomyth

1. Myth and Dream

The connection between myths and dreams is that they are both spontaneous productions of the psyche. Freud, Jung, and other psychoanalysts spent a good part of their careers showing how the much of mythology, including the heroes, stories, and logic, have been preserved in modern times.

Someone dreamed they were fixing the roof when their hammer fell, and accidentally killed his father. He was then comforted by his mother. The human child is psychologically and physically connected with mother and spends a considerable amount of time with her after birth. The child gets aggressive with mother isn’t present, and the father is the intruder to the child-mother relationship.

Both the death and love impulse constitute the foundation of the infamous Oedipus complex. Freud cites the “Oedipus complex” as the reason for why many adults fail to behave rationally. He asserts that every pathological disorder of sexual life should be considered an inhibition to development. Further, every neurotic is either Hamlet or Oedipus. Here is an interesting discussion of the psychological analysis of hamlet.

The unconscious can be terrifying. The imagery and sensations that inhabit your psyche are often inconveniences we would like to live without. But the unconscious contains jewels in addition to the terrors. It contains psychological powers that we have chosen not to integrate into our waking lives. These powers are unrecognizable, until a trigger such as word or smell of a fragrance, produces frantic psychic activity. These ideas are often dangerous, because they threaten our “known” territory. They throw us into the realm of the unfamiliar, but they also hold the keys to the desired but feared journey, to the discovery of the self. The unconscious threatens to destroy the world we live in but promises a reconstruction of a bolder and more pristine life.

The main purpose of mythology and rite has always been to provide the symbols that move the human spirit forward, countering the pull of the incessant human fantasies that tend to hold it back. And it might be that the high rates of neuroticism among us is a result of the absence of effective spiritual aids. We remain fixated to the “unexercised images of our infancy, and hence disinclined to the necessary passages to adulthood.”

“In the United States there is even a pathos of inverted emphasis: the goal is not to grow old, but to remain young; not to mature away from Mother, but to cleave to her. And so, while husbands are worshiping at their boyhood shrines, being the lawyers, merchants, or masterminds, their parents wanted them to be, their wives, even after fourteen years of marriage and two fine children produced and raised, are still on the search for love”

The suggestion here is that both men and women in the U.S fail to grow up, because they have been deprived of the proper myths and rites that would have enabled them to transcend their childhood fixations.

“Apparently, there is something in these initiatory images so necessary to the psyche that if they are not supplied from without, through myth and ritual, they will have to be announced again, through dream, from within—lest our energies should remain locked in a banal, long-outmoded toy-room, at the bottom of the sea.”

Death and Rebirth

“The hero is the man of self-achieved submission. But submission to what?”

That’s the riddle we should try to solve. Professor Toynbee, in his six-volume study of the laws of the prosperity and disintegration of civilizations and of the self will not be resolved by archaism (a return to the old), or futurism (plans guaranteed to create an ideal projected future).

“Only birth can conquer death – the birth, not of the old thing again, but of something new.”

The culture hero’s aim is to dredge up the things that have been forgotten, not only by ourselves, but possibly by our entire civilization. Such a hero is the bringer of boons. And the journey of the hero begins with a retreat from the external world, into the world of the psyche – where the difficulties really exist. And once there, the hero should learn to clarify what those difficulties are and get rid of them. To “give battle to the nursery demons of his local culture) and break through to the undistorted, direct experience and assimilation of what C. G. Jung has called “the archetypal images.””

This is the process known to Hindu and Buddhist philosophy as Viveka, “discrimination.” Viveka is described as a “Sense of discrimination; wisdom; discrimination between the real and the unreal, between the self and the non-self, between the permanent and the impermanent; discriminative inquiry; right intuitive discrimination; ever present discrimination between the transient and the permanent.”

The hero, then, is whoever breaks through his personal and cultural limitations, and finds out the deeper truths about humanity, that reside within our psyche.

Most men and women choose the less adventurous route. They follow unconscious tribal routines. But these seekers are redeemed, by “virtue of the inherited symbolic aids of society, the rites of passage, the grace-yielding sacraments, given to mankind of old by the redeemers and handed down through millenniums.”

In other words, there are two paths to salvation. The first is the exploratory path, that requires you to transcend the limiting beliefs of your own mind and culture. And the second, is a safer path to salvation, that requires you to follow rituals of the past that will guide you in an approximately right direction.

2. Tragedy and Comedy

The purpose of mythology and fairy tales is to reveal specific dangers and take you away from tragedy into the realm of comedy.

3. The Hero and God

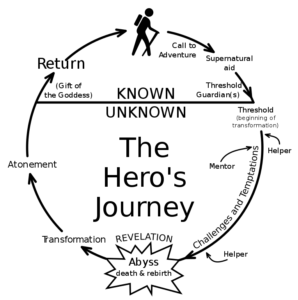

Summary of the stages for the hero.

- “The Call to Adventure or the signs of the vocation of the hero”

- “Refusal of the Call or the folly of the flight from the god”

- “Supernatural Aid, the unsuspected assistance that comes to one who has undertaken his proper adventure”

- “The Crossing of the first Threshold”

- “The Belly of the Whale or the passage into the realm of night.

The stage of the trials and victories of initiation are then represented through 6 stages.

- “The Road of Trials,” or the dangerous aspect of the gods

- “The Meeting with the Goddess” (Magna Mater), or the bliss of infancy regained

- “Woman as the Temptress,” the realization and agony of Oedipus

- “Atonement with the Father”

- “Apotheosis”

- “The Ultimate Boon.

The return and reintegration with society is one of the major challenges the hero faces. It is necessary for the prosperity of society for the hero to make the return – it is a justification for the long retreat of the hero. But like the Buddha, there is a possibility that the bliss he experiences may supersede any interest in going back to society and wrapping themselves up in other people’s problems that may be too difficult to solve.

Typically, the fairy tale hero achieves a local, microcosmic win, and the mythological hero a global, macrocosmic win. The former – often the youngest or most despised child who gains extraordinary powers and prevails over his oppressors, the latter brings back with him the boons that that lead to the regeneration of his society.

4. The World Navel

The final theme in the prologue to The Hero with a Thousand faces is the world Navel. It is described as the point which the universe itself grows from. It is “rooted in the supporting darkness; the golden sun bird perches on its peak; a spring, the inexhaustible well, bubbles at its foot. Or the figure may be that of as a cosmic mountain, with the city of gods, like a lotus of light, upon its summit, and in its hollow the cities of the demons, illuminated by previous stones.”

The figure is either male or female (Ex: The Buddha, the dancing Hindu Goddess Kali) and is either seated or standing on a fixed spot, or tied to the tree (Attis, Jesus, Wotan). The World Navel symbolizes continuous creation.

If you are interested in reading books about unmasking human nature, consider reading The Dichotomy of the Self, a book that explores the great psychoanalytic and philosophical ideas of our time, and what they can reveal to us about the nature of the self.