Table of Contents

Communication Strategies

Communication is a type of war. You can trick some people by disguising your great ideas in ordinary form. Others, who are more resistant and dull need extreme language that is new. Avoid static language, don’t be preachy and overly personal. Your words should spark action, not passive contemplation.

Alfred Hitchcock

Hitchcock’s style was disconcerting to many. He often chose strange ways of getting his point across, rarely using words. Once, he left two actors tied together in handcuffs for hours to induce a natural feeling of awkwardness that would improve the authenticity of the scene.

When Hitchcock was a young boy and got into trouble, his father didn’t yell at him, that would have made the boy defensive. Instead, he quietly let him stay in jail with strange adults. This taught Alfred a lesson he would never forget, the power of communicating without words. In many of his movies, he uses images to convey meaning, rather than extensive dialogue. He believes that only a masterful orator could successfully communicate his message, others need to use images and more primitive means of conveying an idea.

The most superficial way of trying to influence others is through talk that has nothing real behind it. The influence produced by such mere tongue wagging must necessarily remain insignificant.

THE I CHING, CHINA, CIRCA EIGHTH CENTURY B.C.

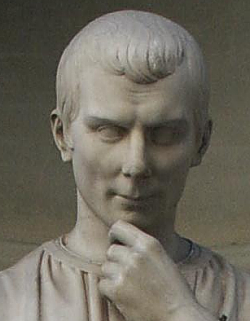

Machiavelli

Niccolo Machiavelli did not have a law degree, and did not come from a powerful family, but he was connected to the Florentine government, who saw great potential in him. He went on diplomatic missions to meet people like Cesare Borgia, King Louis XII and Pope Julius II. But his personal life was not so good, he wasn’t paid well, and while he did most of the hard work, senior ministers took credit for his efforts. He saw many of those above him as stupid and lazy, attaining their positions through birth right alone.

He was developing an art of dealing with these men.

Machievelli was one day sent to prison because he was vaguely implicated in a plot against the Medicis. He was tortured but refused to talk. He was released a year later, in 1513, and retired to a farm in disgrace.

At night he would shut himself up in his study and converse in his mind with great figures in history, trying to uncover the secrets of their power. He wanted to distill the many things he himself had learned about politics and statecraft. And, he wrote to Vettori, he was writing a little pamphlet called De principatibus–later titled The Prince–“where I dive as deep as I can into ideas about this subject, discussing the nature of princely rule, what forms it takes, how these are acquired, how they are maintained, how they are lost.”

Robert Greene, The 33 Strategies of War

He wrote the book to revive his own career and benefit ‘new princes’.

The language in The Prince was strange to his friend, Vettori, it was amoral and very straightforward, it was dispassionate and true. A strange mix at the time. Machiavelli sent the manuscript around to other friends, who did not know what to think of it. It may have been a satirical jab at the aristocracy that Machiavelli often complained about.

The Discourses was another book that Machiavelli wrote, this was a distillation of conversations with friends after his fall from grace. It contained meditations on politics and advice towards the constitution of a republic (unlike the individualistic philosophy described in The Prince).

Even more foolish is one who clings to words and phrases and thus tries to achieve understanding. It is like trying to strike the moon with a stick, or scratching a shoe because there is an itchy spot on the foot. It has nothing to do with the Truth.

ZEN MASTER MUMON, 1183-1260

He later wrote a play called La Mandragola. His first two books, The Prince and Discourses were unpublished but they circulated among the leaders of Florence after his death. In fact, The Prince was published in many languages after he died, and as time passed, it took on a life of its own. The French Cardinal Richelieu made it a political bible. Napoleon used it often and the U.S president John Adams kept it near his bed. Frederick the Great, with Voltaire’s help, published The Anti-Machiavelli, while shamelessly practicing many of Machiavelli’s ideas.

Millions of readers have used Machiavelli’s books for advice on power over the centuries. But could it be that it was Machiavelli who had been using his readers?

Scattered through his writings and through his letters to his friends, some of them uncovered centuries after his death, are signs that he pondered deeply the strategy of writing itself and the power he could wield after his death by infiltrating his ideas indirectly and deeply into his readers’ minds, transforming them into unwitting disciples of his amoral philosophy.

Robert Greene, The 33 Strategies of War

Machiavelli craved the power to spread his ideas. He was denied this power through politics, so he set out to win it through books. He converted readers to his cause and they would spread his ideas, wittingly or unwittingly. Machiavelli knew that the powerful are reluctant to take advice – especially from someone below them in rank. He knew that those who were not in power might be afraid of the dangerous aspects of his philosophy, this would attract and repel many readers at the same time.

To win over the resistant and ambivalent, his books would need to be indirect, strategic, and crafty. He created unconventional rhetorical tactics to get to his readers.

He first filled his books with indispensable advice, practical ideas about power. This draws in all kinds of leaders, since we all think of our self-interest first. And no matter how much a reader resists, he realized that ignoring the book could be dangerous.

This is not unlike the strategy that Robert Greene himself has used throughout his career.

For some time I have never said what I believed, and never believed what I said, and if I do sometimes happen to say what I think, I always hide it among so many lies that it is hard to recover it.

Niccolo Machiavelli, letter to Francesco Guicciardini (1521)